Treatment Overload: Lifting the Burden of Too Much Healthcare. A Simulation of the Healthcare System. 13 November 2019

“It’s March 2020. The Prime Minister has received a report from the Health Minister stating that 30% of Australian healthcare is low value, 10% is harm and 60% is evidence based. ‘This,’ he says to the Health Minister, ‘is a problem. We must do more, with less. We need the whole system to accept the 60:30:10 challenge’.”

That was the simulated scenario that Professor Jeffrey Braithwaite of the Partnership Centre for Health System Sustainability (PCHSS) put to the over 80 health system experts and stakeholders at the Sydney Harbour Marriott Hotel on 13 November 2019.

The “Treatment Overload: Lifting the burden of too much healthcare” event challenged participants to approach the wicked problems in healthcare from a different perspective. Over the course of the four-hour event, the attendees heard from policy makers, health consumer advocates and health system researchers about the state of the Australian healthcare system and the problem of low-value care. Attendees were then asked to take part in the Simulation Game, which was designed to mimic the complexity of the whole healthcare system. Each assumed a role other than their own (for example a doctor played the part of a journalist while a nurse took on a role as a member of the Treasury), as they tried to solve the 60:30:10 problem.

Framing the problem:

Professor Braithwaite, Chief Investigator for the PCHSS, set out the challenge for the day in his opening remarks, saying, “we’re going to simulate the health system and figure out whether we, through the simulation, can make it better.” He then introduced Aunty Donna Ingram, an Elder of the Redfern Aboriginal Community.

After a moving Welcome to Country by Aunty Donna, Elizabeth Koff, Secretary of NSW Health, took the stage to give her perspective on the Australian healthcare system. In her remarks, she emphasised the need to focus on patient-centred care, as well as the crucial issues of financial sustainability, delivering high-quality care in the right place at the right time, prioritising prevention, and driving best practice using data and research.

Consumer health advocate, Tim Benson, spoke next about his personal experience navigating the health care system after being diagnosed with prostate cancer. He expressed the challenges of weighing the different treatment options (from “wait-and-see” to radical prostatectomy) laid out by his healthcare professionals. In the end, he decided to undergo targeted radiation therapy treatment. Tim had a positive outcome (he suffered no long-term side effects from the treatment and is now cancer free) but still undergoes regular testing. He reflected on the time, the cost and the stress of treatment and monitoring and how even now it is not possible to know what the right amount of care was.

Next was the premiere of “The challenge of too much healthcare.” In this 15-minute video interview conducted by Professor Ray Moynihan of Bond University, PCHSS’

Professor Paul Glasziou explained the concepts of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, their causes and what can be done about them. Overdiagnosis occurs when a person is diagnosed with a medical condition that would not have caused harm in the person’s normal lifetime if left untreated. For example, ~40% of prostate cancer and ~20% of all types of cancers are overdiagnosed. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment, or unnecessary treatment, account for almost 30% of the increase in health care spending, creating more burden on the health system. Expanding disease definitions, such as the proposed lowering of threshold for high blood pressure, are also a source of low-value care. Reducing unnecessary testing, weighing the benefits and harms of disease definition changes and reducing medicalisation of conditions are ways to reduce low-value care.

The full interview is available on the PCHSS YouTube channel and an infographic about low-value care is available on the PCHSS website.

The Simulation Game:

The centrepiece of the event was an interactive healthcare simulation game. To prime the participants for the activity, Professor Braithwaite provided an introduction to systems thinking, highlighting how healthcare represents a “complex adaptive system” whose dynamics are not reducible to linear models or responsive to simple interventions. On this note, he concluded: “No one has designed a human system more complex than the health system.”

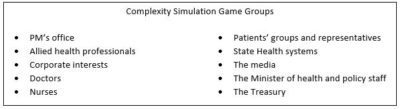

After this, attendees were assigned to one of 10 stakeholder groups and the game began. Real-life doctors and researchers were asked to imagine being

health journalists, while real-life consumer health advocates and hospital administrators took on the role of health ministry officials. Then, after almost an hour of stepping outside their spheres of expertise, the stakeholder groups presented their recommendations.

Insights and recommendations from the simulation game:

The “Patients’ groups and representatives” focused on education and awareness saying that health consumers don’t often know the true costs of treatment.

The “PM’s Office” suggested a constitutional referendum to create a single-payer system.

In order to help save money, the “Treasury” recommended a focus on primary care – for example, through the creation of stakeholder panel dedicated to curbing avoidable hospital presentations. They stated that the money saved could be reinvested in the system.

In a similar vein, the “The Minister of Health and Policy Staff” proposed increasing preventative care and ‘hospital in the home’ services, as well as focusing on greater transparency to identify sources of low-value care.

The “Nurses” commented that they “work where doctors won’t go” and believed that their role in the healthcare system should be expanded – that the system should “lift the ceiling” on the types of treatments that they can provide. They said that treatment should “come from the right place” and, given their place on the frontlines of healthcare, they were well positioned to assist in this regard.

The “Allied Health Professionals” highlighted the importance of their role in increasing productivity by getting people back to work. They recommended new evaluation models of care to know where to invest and disinvest based on what is working.

On a related note, the “Corporate Interests” group described an eagerness to direct their resources toward data analytics, precision medicine, and big data in order to understand the exact needs of each patient and to increase the value of every health dollar spent.

The “Media” group – who spent much of the simulation game pressing the government and other health institutions for answers to their questions – ended up proposing an ambitious media campaign and television series entitled, “War on medical waste”. Their focus would be on promoting health literacy among the public by telling patients’ stories. They also hoped to link healthcare issues with the subject of climate change and touched on an interest to advocate for the creation of a single-payer system.

The comments of the “Doctors” centred on the problem of silos in the health system; citing the need for an integrated health system.

At the conclusion of the game, the question of silos was taken up again as one of the central lessons of the game itself. In his concluding remarks, Professor Braithwaite noted that it took 40 minutes out of the 55 minutes allocated to the game before any of the stakeholder groups decided to get up from their tables to go speak with members of any of the other groups. He said that this was very representative of the real healthcare system, and given the system’s complexity, it is only through communication and collaboration that we will be able to address the problem of overtreatment and the many challenges that healthcare faces. “People tend to stick to their stakeholder group,” he said, “but these problems can’t be solved by any one group.”